Peter Bjuhr Composer

The concept of default performances

2014 August 20

A while ago in a series of posts Tim Davies argued that many scores these days are over-notated, and introduced the concept of the default interpretation or performance. The basic idea is that by notating what the players would do anyway by "default" you're wasting your own time as a composer/arranger/orchestrator and distracting the players. (Check out deBreved).

I find this whole idea very interesting. Furthermore it's a bit counter to what I have been taught, which centered much about clarity and avoiding questions.

Redundant information

Let's start with a very simple example to explore this idea: if you are writing music for strings (let's say a string quartet) arco is the default playing technique, so it would be totally redundant to include the text 'arco' on top of the score. Only if you have a previous 'pizz.' marking it would make sense to add an 'arco' marking. With Tim Davies terminology we could say that to put 'arco' at the start is an obvious example of not knowing the default.

This example is somewhat trivial but it's a good starting point because here I think not many would disagree with Tim Davies in trusting the default and omitting the 'arco' mark at the start of the piece.

Counterproductive information

To expand on Davies point I also think that one can find examples where trying to notate the default would be not only redundant but even counterproductive. I'll give an example which I think is quite relevant and clear:

The default for the string players would include some amount of vibrato so therefore it would be productive to give the instruction 'non vibrato' (or senza vibrato) which would give no vibrato (or at least less than the default amount). It would also be productive to call on 'molto vibrato' to have more vibrato than default.

But would happen if you give the instruction 'vibrato' in the hope of getting the default vibrato? I'm pretty certain that the performer will give you more vibrato than default just to make sure. But if you write 'poco vibrato'? I'm pretty certain that this will result in less vibrato than default (but not as little as 'non vibrato').

The best way to make certain that you get normal vibrato is to explicitly call for normal vibrato (or something equivalent such as vib. norm, vib. ord). This is also recommended notation when you return from a non-default vibrato (see Gould: Behind Bars pp 146-147). You can give this instruction without risk of being counterproductive, but it is perhaps even more obviously redundant than an 'arco' marking (if used without any previous non-default playing).

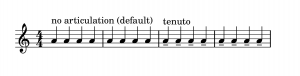

I'd also like to add another example: For strings the default without any articulation marks is to change bow direction with each note and to add no space between notes. Let's not even go into the bowing but only ask - can you notate this default articulation with any combination of articulation marks? I think the closest thing would be to add tenuto marks but that would imply slightly more emphasis on each note.

Changing standards

It's time to look at this concept of the default from a more critical perspective. Things change, one cannot assume that what is default performances today will remain default forever. Earlier it was stated that 'arco' is default playing technique for string players (or at least for the string quartet in the example) but there's an example where this has changed; if you play jazz style contrabass, pizzicato is obviously the default instead of arco.

Wouldn't it be better to try to anticipate these changes of standard and try to be more precise in the notations? Then the score would be future secured. It's hard not to find this objection convincing, but it seems to me that it misses the fact that the notation standard change as well as the performance standard. If early music were more precisely notated would it be more easy for today's performers to do it justice? Yes, perhaps but only given that we could interpret the meaning of there symbols correctly. As musical notation is a form of communication I think it's better to focus on the communication with contemporary performers and only hope that future performers will do it justice (if at all). Furthermore if you really want to make sure the future will perceive the music as you want them to, you should make a good recording that gets preserved.

No default

So far I haven't raised any major objections to the idea of the default. But I think there's one comment that has to be made. It doesn't seem to me that there are defaults that cover the whole range of musical notations. The most obvious counter-example to me is dynamics. With the exceptions of instruments like the organ or harpsichord that doesn't suit well for dynamic considerations, you have to notate what dynamic level you're aiming at. There isn't any dynamic level that will take precedence.

At the moment I don't have any more examples of notation contexts where the idea of a default doesn't apply. If you have some additional ideas on this please write a comment below!

Conclusion

If we imagine a score with the bare essentials needed for a performance. We can assume that it contains pitches and durations. It would also contain some tempo indication. I've also argued that it would have to include some information about the dynamics. Maybe there also need to be some more information. What we're after is some score that contain all information needed for a non ambiguous performance (hence no questions) but which contains no more specific performance instructions. The view is then (following Tim Davies proposition) that we should add only those performance instructions to this basic score that would change the performance (compared to the performance of the plain score). All other indications are redundant, or worse - misleading and counterproductive.

Behind Bars by Elaine Gould

2013 August 09

I've started to study Behind Bars by Elaine Gould. "The definitive guide to music notation", according to the subtitle. And in a foreword Sir Simon Rattle affirms this view:

"Elaine Gould, in this wonderful monster volume, has written the equivalent of the Grove Dictionary for Notation. It is an extraordinary achievement, and if used by the next generation of composers and copyists will be a blessing for hard-working and long-suffering performers everywhere! Every chapter presents solutions and rules that will make our life easier, save rehearsal time and frustration, and will ultimately lead to better performances. What is important for a musician is to be able to spend rehearsal time on the music itself. I not only welcome her book unreservedly, but I would also pray that it becomes a kind of Holy Writ for notation in this coming century. Certainly nobody could have done it better, and it will be a reference for musicians for decades to come."My first impression is also very promising. I'm sure I will post some more during my reading of it.

Creative commons and cultural sharing

2013 April 09

First an important note before I go into more details of the creative commons licenses: authors, artists, composers and creators and originators in different fields are learning more about how to share their creations and the creative commons licenses are providing them the means for legally doing so. Please do advocate that more should go in this direction, if you like. But don’t be impatient, do respect the decisions of the creators and most importantly don’t encourage unauthorized sharing! But now let’s learn some more about creative commons. Let’s start with this introductory video:

- [embed]http://vimeo.com/25684782[/embed]

- Creative Commons Kiwi by Creative Commons Aotearoa New Zealand is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 New Zealand (CC BY) license. The video was made with support from InternetNZ and is a project of the Royal Society of New Zealand. Produced by Mohawk Media. http://creativecommons.org/videos/creative-commons-kiwi

What is art music?

2012 June 13

Art music (also known as serious music, legitimate music, concert music, or erudite music) is an umbrella term used to refer to musical traditions implying advanced structural and theoretical considerations and a written musical tradition. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_musicWhen you're deeply involved in making so called art music, its only natural to at some point ask the question “what is art music?” and further “what is the difference between art music and other forms of music?”. Perhaps the phrase 'art music' is not so widely used, but for me this concept is of greater relevance than others, e. g. contemporary classical music. My main point in this preliminary attempt to answer will be that the difference is not a question of stylistic differences but instead a question of attitude; the ambition of anyone making art music either as a performer or as an originator should not be to imitate the style of other music but to have an artful attitude towards ones task. That is not to deny though that art music can have a relation to other art music or other music overall; I don't think one can nor is it desirable to create in a vacuum. If this could be agreed upon, that if you have the right artful attitude in the creation the stylistic options are of secondary nature; we have nevertheless not come especially far – we still need to know a lot more of what this attitude could be. As seen in the short quote from Wikipedia in the beginning “Art music” is sometimes equated with “serious music”. Can this tell us something about the attitude, i. e. should we have a 'serious' attitude towards art? I would be deeply hesitative towards making this claim. But what I do would like to bring to the formula of the attitude we are seeking, is that we should think that art music is something important. So, not an 'serious' attitude but rather a sense of something important, or significant. If I may further expand on this, we might add the criteria that the importance or urgency should not only be important for me or you - but on a much more general scale. I hope you realise that this is increasingly more difficult and that people involved with art music, including myself, sometimes fail meeting this criteria. I also feel that I should comment shortly on the other “also known as” in the wikipedia quote above. “Legitimate music” - that some music can be more legitimate than other is for me foreign. “Concert music” - any music could potentially be presented in a concert. As a concept it is not especially clarifying; “Art is what is presented in art galleries.”, “concert music is what is presented in the concert halls.” “Erudite music” - this concept is not familiar to me, but it seems that the general idea like with legitimate music is to give a high evaluation of certain music. I think though that it is vital not to mix the categorisation of music and the evaluation of the same; after you categorised the music as belonging to a certain category it should still make sense to ask if the music is good or bad. In my mind nothing of this take us any closer to the core of art music. Next up I think we have to realise that the concept of art itself has changed over the course of history. So we could if we wanted differentiate between different attitudes for different historical periods. At the moment I'll settle for the simplistic description that art was in the past more judged for the craftmanship behind it and today it's more judged for the ideas and thought behind it. But in either case I think we have to again make the point that it is the attitude and intention which is of importance here; you can only fail to deliver an excellent piece of art if your intention has been to create such a thing in the first place. If you just whistle a tune its not intended as art music and should no less be judged as such. Admitting that the art-concept has changed its focus the most interesting would be to explore the attitude demanded by art today, even if it still would be interesting to find out how this was different in the past. I would roughly say that having an open mind and trying to see things from a new perspective is the attitude we are looking for. To be involved in art music is I suggest to be to share the artistic attitude common to other art forms. What this attitude is is not fixed and stable for all times, but there has for a long time been a consequent wish to create an other roam separatad from the ordinary and the common. Today art fill the purpose of leaving the ordinary by means of new interesting ideas and perspectives on our world and our our perception of it. I would say that it is not change our novelty for the sake of change or novelty, but to because this change or novelty is deeply felt as important. I will not attempt to suggest that this will be the final answer on what art music is, not even on this blog. Please leave a comment if you agree or disagree or has some thoughts of your own!

File sharing simplified

2011 September 28

I've finally got started with SoundCloud, and when using the upload function I realised that this could be a great illustration of how simple the question about file sharing really is:

When uploading you choose between 'all rights reserved' or 'creative commons' for the license of the uploaded file. Then you can also choose if others are allowed to download your clip or not. But legally the license question is the vital question for how your soundcloud clip is allowed to be shared and spread. Without going in to exactly how the different license options work, I would like to state it as simple as this – if you want your audio clip to be able to be shared by anyone, choose 'creative commons'; if you do not want this, choose 'all rights reserved'. (I'm assuming here that you have full rights to the stuff you're uploading in the first place.) For the user/listener the point can be stated even more simple – if the copyright owner allows sharing, feel free to share as much as you want; if the copyright owner does not allow it, please respect that!

Please comment on this if you're of another opinion or if you think I'm missing out on something!

Cage and non-intention

2011 September 08

I'm currently reading John Cage:s Composition in Retrospect. It is mostly written in his characteristic “mesostics”, a form of art text with linked lines of prose poetry.

A key word in Cage:s production is 'non-intention'; he wanted to free himself from “memory, taste, likes and dislikes”.

He often used chance operations to attain non-intention, but also other methods. I'm very intrigued by this idea, although I do think that Cage took it to the extreme. I will defenitely go back to this later, but compare if you like this to my previous writing about choice, chance and rules.

I'm currently reading John Cage:s Composition in Retrospect. It is mostly written in his characteristic “mesostics”, a form of art text with linked lines of prose poetry.

A key word in Cage:s production is 'non-intention'; he wanted to free himself from “memory, taste, likes and dislikes”.

He often used chance operations to attain non-intention, but also other methods. I'm very intrigued by this idea, although I do think that Cage took it to the extreme. I will defenitely go back to this later, but compare if you like this to my previous writing about choice, chance and rules.

Mendelssohn and the music of the past

2011 August 31

It was said of Mendelssohn that he was too fond of the dead, when he frequently performed older music. Where is that attitude today? It seems to me that today too much effort is put in preserving the great tradition from two centuries back. I don't blame Mendelssohn for contributing to this interest in the music of the past. I just wish that the demand for new interesting art music could be greater in general.

Contemporary trends of expanding the concept of remixing

2011 January 10

Previously the concept of remix was mainly related to “[...] audio mixing to compose an alternate master recording of a song[...]” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Remix). But in contemporary art music the ideas behind the remixing and sometimes also the word “remix” has lately been used also on purely acoustic composing processes. And often this involves reusing music from the old masters in a remixed form. To reuse others music in art music is of course nothing new in itself and has been done extensively in the past (often in the form of a variation). But when you borrow both the concept and more importantly the attitude from the more popular remixers it undoubtedly amounts to something new. Apart from the freshness of these forms of remixes, I am mostly interested in the connection with similar approaches in other art forms.

“A remix may also refer to a non-linear re-interpretation of a given work or media other than audio. Such as a hybridizing process combining fragments of various works. The process of combining and re-contextualizing will often produce unique results independent of the intentions and vision of the original designer/artist. Thus the concept of a remix can be applied to visual or video arts, and even things farther afield. Mark Z. Danielewski's disjointed novel House of Leaves has been compared by some to the remix concept.”

“A remix in literature is an alternative version of a text. William Burroughs used the cut-up technique developed by Brion Gysin to remix language in the 1960s.[2] Various textual sources (including his own) would be cut literally into pieces with scissors, rearranged on a page, and pasted to form new sentences, new ideas, new stories, and new ways of thinking about words.”

“A remix in art often takes multiple perspectives upon the same theme. An artist takes an original work of art and adds their own take on the piece creating something completely different while still leaving traces of the original work. It is essentially a reworked abstraction of the original work while still holding remnants of the original piece while still letting the true meanings of the original piece shine through. Famous examples include the Marilyn prints of Andy Warhol(modifies colors and styles of one image), and Weeping Woman by Pablo Picasso, (merges various angles of perspective into one view). Some of Picasso's other famous paintings also incorporate parts of his life, such as his love affairs, into his paintings. For example, his painting Les Trois Danseuses, or The Three Dancers, is about a love triangle.”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RemixAnother example from pop art is Roy Lichtensteins reuses of iconic images from comics.

Many times have I had the notion of using older music in an iconic way.Roy Lichtenstein, Whaam! (1963). On display at the Tate Modern, London. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Postmodern_art)

Music with information?

2010 October 19

Music certainly has the ability to affect the listener, but can the reaction be controlled? Can music even contain information or a message to the listener? Even if we agree that (instrumental) music don't normally contain information, is it possible in some way to create music that does? Can music contain a code that can be decoded by the listener? For the moment I just state these questions. I will go back to them later. Feel free to supply thoughts and answers via the comments.

Conceptual art - definitions and distinctions

2010 October 11

As you may have read here before, I am very interested in conceptual art and its possible application in music. A basic description of conceptual art would be that the ideas or concepts behind the art work takes precedence over concerns about aesthetics and craftsmanship. Traditionally aestheticism and craftsmanship have been very highly rated so a radical form of conceptual art would be to diminish these considerably. A famous and early definition of conceptual art by Sol LeWitt stated:

In conceptual art the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work. When an artist uses a conceptual form of art, it means that all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair. The idea becomes a machine that makes the art.So basically we could say that in a radical or true form of conceptual art the execution of the ideas is merely a trifle. From this it can´t really be concluded though that the execution is swift. And it can´t even be concluded that the execution doesn´t involve craftsmanship. But one way to make clear the shift from the aesthetical to the conceptual is an apparent lack of (traditional) artistic skills in the work. (In talking about artistic skill we have to appreciate though that conceptual art involves new and different artistic skills.) All art forms has been and are in constant change. In my view conceptual art no longer needs to be made in its most crude or radical form; for me it is interesting to combine traditional artistic skills with the new conceptual artistic skills. But even older more aesthetically and artistically driven art of course included ideas, so to be called conceptual the precedence of the idea has to be maintained. In some if not all of my latest works I have permitted the aesthetical and stylistic choices to be totally dominated by the fundamental idea or ideas, i. e. if the idea have demanded a certain kind of music I have not hesitated in my ambition to create that kind of music or sound world. I would also like to make a distinction between what would be "conceptual" in a more strict sense, i. e. actually involving concepts; and more idea driven conceptualism not actually involving concepts. Many conceptual works has of course been "conceptual" in this stricter sense, even solely involving words and concepts. But I have not seen the distinction being made. Several of my recent works have also been conceptual in this stricter sense. I would like to conclude with a comment on a previous post. Here I stated my belief in what I called conceptual neoestheticism. The idea could briefly be described as an idea-driven return to more aesthetical music. I would (again) like to clarify this: The term "neoestheticism" assumes a crude view which could be applied to much of the post-modernistic movement - the view that the modernistic movement was not interested in aesthetical considerations and that post-modernism implies a return to pre-modernistic views on aesthetical values. At first glance you could very easily come to this conclusion, which I now think is a mistake. My current view is that the modernists were not anti-aesthetic - they were merely "anti" the aesthetic view that preceded them; I think we must conclude that they clearly had a very specific aesthetical belief-system. What then happened when what has been labelled "post-modern" ideas came in to play, was a remission of the modernistic approach; a more liberal view where in its extreme forms everything is aesthetically acceptable. The return to some aesthetical ideas of the past is I think a result of this relaxation and a symptom for the strong distancing of the past by the modernists. Put in this way my approach of allowing the ideas to rule the aesthetics is perfectly post-modernistic.

Art, Music and Politics

2010 September 20

Yesterday we had a national election here in Sweden, and this have lead me to think of my relation, as a composer, to politics. As I have written before, and perhaps can get back to soon, I think of contemporary art music as being essentially about ideas and not about craftsmanship. (But craftsmanship can still, as ever, be essential to being able to express and realize the ideas.) Hence I think that art music should follow the general direction shift in art itself from being about aesthetic values to being more about concepts and ideas. (This is of course a very rough description of the development over the last century or so, but I hope you agree with me on the general outline.) Given this general attitude of mine, the question can essentially be put as being about the relation between art and politics. As I see it art can and should be political. But, and this is important, it should take into account the big issues about humanity that are most strongly felt and it should keep unconditionally impartial towards political organisations.

Greater demand for new music in the future?

2010 August 20

Even for the audience that is skeptical about the post-Mahler music I assume there is a demand for new music. Even if there is a vast source, it is still limited and growing older and supposedly more distant from the performers and listeners. I myself have a fascination for the 19th century which I think I have in common with many of the lovers of the music from that period, but I think there also must be a need for expressions that is closer to our lives today in the 21th century. If we assume the demand above and also assume that the contemporary music have a demand for a greater audience, when will this two demands meet; when will we see a greater demand for new music? Tell me what you think...

Can a computer create music?

2010 January 04

When I use the dubious concept of computer-generated music (most recently here), a remark is in its place: A computer is just a tool, although an excellent one; a computer can't create music. The creator if any is the programmer/composer which uses the computer tool. Here again I think the concepts of rules, chance and choice can be useful in explaining the idea: The programmer/composer chooses which rules that are to be used and much other things. The programmer/composer also chooses which elements of the music that are to be governed by chance. The impression that the computer in fact creates the music, is perhaps enhanced by an extensive use of elements of chance. When the music clearly isn't by human hand it is easy to attribute it to the computer. But again the computer is just a tool and similar result could potentially be produced by another less powerful tool, e.g. a dice. The important thing in this case is I think that the programmer/composer is choosing where chance is applied.

The Idea

2009 November 26

I think the most important part of a composition is the idea behind it. The craftsmanship is also important but at this point in history there is of course vastly amounts of music already; and to justify the creation of more music I think you have to back up with a pretty good idea. What then is the nature of this idea that I seek? I have previously written about musics current relation to art (e.g. art and music and music art) and I think it is very interesting taking a conceptual artists view in creating the idea. But the idea can also be of a more esthetic nature (compare with a clarification). A conscious limitation can be an interesting start; to use chance or rules can also be interesting from a conceptual or esthetic point of view.

choice, chance and rules

2009 November 25

I promised to write more about choice and chance. And now I think I have found the piece of the puzzle that I was looking for - rules. Choice, chance and rules. Let me try to summarize the thoughts behind this rather abstract formula (I write here about creating music but perhaps this could be applied to all creative processes): When you create music, more or less consciously, you make choices you follow certain rules and you leave certain elements to chance. I am currently involved in a project about computer music. I think this phenomena can be a clarifying example, because it makes all processes more clear (at least for the person making the programming). You can use the computer to carefully choose every little detail, you can use the computer to make same parameters random (Aleatoric music) or you can use the computer to govern the music by rules (Algorithmic composition).

Limitations

2009 July 14

Before and during composing it is very interesting to set up limitations of some sort. In fact it is very hard to compose if you don´t limit yourself in any way; if you have all the instruments and all the musical possibilies actually available to you, where do you start? Bach of course was a master in composing under strictly limited conditions, e g composing a fugue. This also relates to a previous post about choice or chance (where I promised to write more about its subject). It can be very interesting to use chance to set up ones limitations. Cage were, as I wrote in the previous post, very interested in chance. He was also very interested in natural or accidental sounds and their relation to "music", and used chance to investigate that relation. I am inclined to be more interested in using actual choices to set up the limitations - to use experience and judgment. I will get back to this (again) and write more about different limitations.

Musical references

2009 July 07

I´m interested in references to other works, styles and genres. Historically art music have often involved references to other periods and to other genres, i. e. folk music. Art music had also within itself a strong tradition to implicitly and explicitly refer to, e. g. when writing a symphony the composer in a way refers to all other symphonies ever written. In the high modernistic period (which I consider ended by the way) it was something of a taboo to use this kind references. At least was the end to make a clean start from tradition. But, although originality was a important virtue and the break with history was a important goal, modernism I believe was a tradition in itself. The fear of references ended with Schnittke and other pluralists using direct musical quotations in their works. Another 20th century movement has to be mentioned in this context - the neoclassical direction with its references to the classical, pre-classical and baroque periods; here references took an even more important role than in previous music, perhaps as some kind of reaction to the ahistoricism of modernism. Today contemporary music (and even more strongly contemporary art) is widely diverse in artistic styles and methods. It is as the modernistic project succeeded in its radical goals of originality and rootlessness, but ended up finishing off itself in the process; when the modernist direction finally suceeded in killing tradition there could exist no gathering movement and hence modernism had dematerialized itself. (This reflection I think is absolutely true regarding art, but regarding music modernism still takes its dying breaths.) When tradition is dead and pluralism rules, references takes on a new role. You have the whole spectra from provocative appropriations and interventions to mere subtle implications of aspects of obsolete or popular cultures.

Choice or chance

2009 May 31

I´m interested in Cage´s methods of incorporating chance in music, but whenever I want to use chance as a factor in a composition I tend to go for choice instead. Let´s say that I would have six alternatives and I am thinking of using chance. But instead of throwing a dice to get a totally random result, I would tend to choose which of the six alternatives I prefer. I think that there is something fundamentally interesting here; let me get back to this... (To be clear, Cage used both choice and chance in his compositions.)

Music Art

2009 March 16

The concept of sound art is well known:

Sound art is a diverse group of art practices that considers wide notions of sound, listening and hearing as its predominant focus. There are often distinct relationships forged between the visual and aural domains of art and perception by sound artists. Like many genres of contemporary art, sound art is interdisciplinary in nature, or takes on hybrid forms. Sound art often engages with the subjects of acoustics, psychoacoustics, electronics, noise music, audio media and technology (both analog and digital), found or environmental sound, explorations of the human body, sculpture, film or video and an ever-expanding set of subjects that are part of the current discourse of contemporary art.[1] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sound_artI propose to use a new concept - music art - as a form of sound art where musical sounds and structures are used in artistic practises.

A clarification

2009 February 07

In the latest post I defined myself as some kind of conceptual neoestheticist. But I think that both this choice of words and the actual view behind it needs some clarification. I would define neoestheticism as a renewed interest in esthetic values. This does not necessarily mean a renewed interest in some previous esthetic system, as a concept like neoclassicism would imply. Conceptual art could be defined as art were the abstract thought and ideas behind it takes precedence over the esthetic value; or as art were the abstract thought and ideas behind it takes precedence over the craftmanship in making the art. Both these definitions could in a way be in opposition to my supposed integration between conceptualism and estheticism. I would instead define it in less opposing terms. Conceptual estheticism or conceptual neoesteticism is then by my use of it the theory that abstract thought and ideas and esthetic values both are important in the creation of art and music.

Art and music

2009 February 07

Art and music have always been connected; but when art was painted by artists on canvas or some other material and music were played by musicians on instruments, there always were a gap between them. Now this gap is not as self-evident any more. Now artists are interested not only in the visual but also in the audial. And composers have a growing interest in the conceptual aspects of their works. I like to combine conceptual ideas with a neoesthetic approach.

Art music today

2008 November 11

As a representative for C-Y contemporary I was recently asked to describe the status of artmusic today; a task I find very stimulating. I think that we in C-Y have a very clear picture of what we are doing so the question wasn´t difficult to answer: First, and perhaps most importantly we have an integration of art and music under the concept of sound art. Secondly we have influences from other genres, were free jazz and electronica are perhaps those most closely related. But we have also now more references to older forms of art music. Artmusic is today more eclectic than ever before. In both characteristics above electronic music in different forms play an important role. These two are as I see the most recent trends. But naturally ideals from the two major movements of the twentieth century, modernism and minimalism, still lives on in our century.

Open source

2008 September 15

Today I discussed a new piece with the performers. It is a very open piece called The Eight Elements for two percussionists. It is always awkward presenting a score that is simplistic and open. There is often a natural inclination to show of one´s skills as a composer. But the performers almost always like when they are given space. For me it is important to as far as possible adapt the music for the musicians. And if you go too far into the details, you risk reducing the musician from a performer to a mere executor. Don´t get this remark wrong; it is not to be nice to the musicans (even if that can be good too :) ), it is because the sounding result will be better - the best music is created, I think, when both the composer and performer contributes their part to the whole.

Imagining sounds

2008 September 12

My latest post on the projects blog raised some questions about working with sound tools when composing. Composing have often required the skill of imagining different or even all aspects of the music without beeing able to actually hear them; it wasn´t so strange that Beethoven could continue to compose even after he had gone almost completely death. When now the notation programs are offering better and better simulations of the written score, less and less of these simulations need to take please in the composers head. And the magic is partly gone forever. But I can´t see how the traditional skills of the imaginative composer can be a burden. If you depend solely on the computers output it will be some kind of time consuming trial-and-error-technique. Furthermore, the composers possibilities to market a new written score are increasing greatly when he need not depend on others having the same skills as himself.

Peter Bjuhr Composer

Here I publish information of the music I've written. I also blog about my projects and thoughts about music in general.

I am a contemporary classical composer and compose music for classical musicians, but as you can see from my worklist I've also done other things - including live electronics, electroacoustic music (eam) and music for other types of ensembles (e.g. a jazz trio).

My works have been performed globally, including Europe, Asia and North America.